JUNE 2006

BRONX RIVER ALLIANCE

One Bronx River Parkway

Bronx, New York 10462

718-430-4665

www.bronxriver.org/plans

Project Partners

The Bronx River Alliance initiated the Greenway Plan to present a full vision of the Bronx

River Greenway. As we advance this plan, the Alliance will work closely with the New York

City Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks) to develop the greenway as a new

flagship park within the New York City parks system.

This plan represents years of collaboration by the Alliance and its partners, including the principle implementing agencies of the greenway: NYC Parks (Bronx Borough, Planning and Capital Divisions) and New York State Department of Transportation. This document is indebted to the crucial and substantial expertise both agencies provided during this planning process.

The development of this plan was guided by the Bronx River Greenway Team, who formally and informally gave input on its content. Especially helpful was the input of Colleen Alderson, John Bachman, Linda Cox, Resa Dimino, Rich Gans, Russ LeCount, James Mituzas, Gail Nathan, Roger Weld, and Dart Westphal. Parks Commissioner Adrian Benepe's comments were extremely useful at the Parks review, as were those of Bronx Borough Commissioner Hector Aponte, First Deputy Commissioner Liam Kavanagh, and Deputy Commissioner Amy Freitag. This plan was also reviewed through a series of community meetings and discussions. We thank the hosts of these meetings: Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice, the Bronx River Art Center, and Community Board 12.

The following pages of the greenway plan outline the considerable progress Alliance partners have made in realizing the vision of a continuous Bronx River Greenway, as well as the unmet challenges and obstacles that lie ahead. Progress to date is made possible by the dedication of Alliance partners and by the myriad federal, state, and local organizations that have generously funded our work. For a list of Alliance partners and funders, go to www.bronxriver.org/whoWeArePartners.cfm.

This plan would not have been possible without Greenway Program support from the Altman Foundation, The J.M. Kaplan Fund, Merck Family Fund, The New York Community Trust, and Sarah K. de Coizart Article TENTH Perpetual Charitable Trust.

Authors:

Joan Byron, Pratt Center for Community Development

Maggie Scott Greenfield, Bronx River Alliance

|

|

|

Dart Westphal, Chairperson Linda Cox, Executive Director/ Bronx River Administrator Joan Byron, Greenway Team Co-chair Gail Nathan, Greenway Team Co-chair |

City of New York Parks & Recreation Michael R. Bloomberg, Mayor Adrian Benepe, Commissioner |

TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INTRODUCTION • 1

- GREENWAY ROUTE: SOUTH TO NORTH • 2

- GUIDELINES FOR ECOLOGICAL PERFORMANCE • 3

- MAINTENANCE AND OPERATIONS • 4

- PROGRAMMING AND ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT • 5

-

APPENDICES • I

(Greenway Design Standards)

-

APPENDICES • II

(Guidelines for Incorporation of Art)

BRONX RIVER GREENWAY HISTORY AND CONTEXT

As you read this plan, the Bronx River Greenway is already taking shape. The greenway is not only an eight-mile-long bike/pedestrian path, but a new linear park in the heart of the Bronx, providing access to the river itself, and bringing green space to communities that have long lacked it. The greenway is a collective response to many decades of abuse and neglect of the Bronx River, and of the communities that line its banks. The Bronx River Alliance, founded in 2001 to work in partnership with the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks) to plan and implement the greenway, is both the heir to the 27 years of restoration work begun by the Bronx River Restoration Project in 1974, and the legacy of a new generation of Bronx activists, dedicated to restoring and protecting the Bronx River as the heart of a living ecosystem, and a vital community.

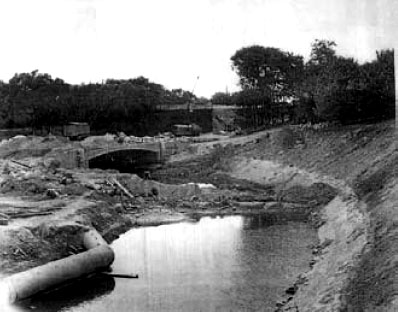

Beginning in 1639 with the purchase by Jonas Bronck of land along what the Mohegan Indians called Aquehung, the river of the High Bluffs, the Bronx River was settled, farmed, and industrialized. Its valley became a corridor for roads, railroads, and highways that connected a sprawling region, but isolated the watershed's communities from each other and from the river itself. The construction of the Bronx River Parkway in the 1920s established the Bronx River Reservation as a decorative landscaped border for the enjoyment of pleasure drivers in Westchester County. The creation of Bronx Park in 1888, as well as the establishment of the New York Botanical Garden and the Bronx Zoo, ensured some protection for the river, though the Zoo and the Garden now restrict most access to paying visitors. South of the Garden and the Zoo, the river was polluted and abused, and its banks were bulkheaded and largely barricaded by industrial uses. The channel itself was repeatedly altered, most recently in the mid-1960s when Robert Moses shifted the river to make way for the Sheridan Expressway. Reconstruction of the Bronx River Parkway during the same period left sections of the river, such as Muskrat Cove near the border with Westchester County, inaccessible and abandoned.

The Bronx River Alliance is working to bring the Bronx River back to a fishable and swimmable state.

The construction of the highway system—including the Sheridan, Cross-Bronx, Bruckner, and Major Deegan Expressways—physically fragmented the Bronx and helped to usher in the decades of abandonment and disinvestment that made the South Bronx an icon of urban decline in the 1970s and 80s. Residents who stayed behind, however, were determined to rebuild their neighborhoods—and to reclaim the Bronx River. In 1974, Bronx River Restoration Project was incorporated, with Ruth Anderberg as its first director. Bronx River Restoration mobilized to remove tons of debris from the shoreline in the 180th Street/West Farms area. Drew Gardens, planted just south of East Tremont Avenue by Phipps Community Development Corporation in 1995, marked the Bronx River as an asset to be restored and cherished.

Construction of the Bronx River Parkway in the 1920s altered the path of the Bronx River.

Still, young people born and raised within yards of the Bronx River grew up without being able to see or touch it. In the mid-1990s, Jenny Hoffner, then a project coordinator for Partnerships for Parks, reached out to a new generation of local activists who embraced the reclamation of the river as an element of a broad struggle for environmental justice. In 1997, these grassroots organizations joined with Partnerships for Parks and other units of NYC Parks, the National Parks Service Rivers and Trails program, and the Appalachian Mountain Club to convene the Bronx River Working Group. As an informal, unincorporated coalition, the Working Group was able to tap the strengths of supporters within and outside of government and worked with NYC Parks to draft the Bronx River Action Plan in 1999. First among the plan's five Core Goals was the creation of the Bronx River Greenway. 1

Riders of the 2/5 train can catch a glimpse of the Bronx River from the elevated line in West Farms.

The Bronx River Action Plan delineated a vision for the greenway that identified sites to be acquired, developed, and linked to existing parkland to create a continuous route. The plan proposed capital projects and matched these with diverse sources of funding, including the New York State Environmental Bond Act, and federal transportation funds,2 among others. The greenway was conceived from its inception not only as a pedestrian and bicycle route, but as a linear park that would serve a population long deprived of green open space and waterfront access. The Bronx River Working Group's ad hoc nature and its creative coordination of resources were keys to its success in launching this audacious project.

The Bronx River Working Group grew to include over 60 community organizations, government agencies, businesses, and institutions. Members' complementary strengths moved the greenway forward. Agencies mobilized in-kind resources to support clean-ups and channeled small grants to community projects. Elected officials committed city, state, and federal funding that now totals over $120 million to Bronx River greenway and river restoration projects, many of which were identified by the Working Group. 3 Activism by local organizations, notably Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice, Sustainable South Bronx, and Mosholu Preservation Corporation, won important victories, including the addition of the Concrete Plant site to the greenway.

As the greenway gathered momentum, the Working Group recognized the need to formalize and staff its work. The dozens of individual capital projects that will realize the greenway are being implemented by different agencies—principally NYC Parks and the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT)—and require the cooperation of many others. The Working Group incorporated as the Bronx River Alliance in 2001, with a mission "to serve as a coordinated voice for the river and work in harmonious partnership to protect, improve and restore the Bronx River corridor and greenway so that they can be healthy ecological, recreational, educational and economic resources for the communities through which the river flows." 4

| 1 | Bronx River Action Plan. October 1999, New York City Department of Parks & Recreation, in cooperation with Waterways and Trailways. |

| 2 | Specifically from TEA-21 funds, the Transportation Enhancement Act for the 21st Century. For more information about TEA-21, see www.fhwa.dot.gov/tea21/. |

| 3 | The Bronx River Working Group not only conceived and began work on the greenway, but also laid out a framework for the ecological restoration of the Bronx River. The Working Group introduced thousands of people to the river through imaginative public events, outreach to local schools, and the publication of the Bronx River Map and Guide. For a more complete description of its work, visit partnershipsforparks.org/wedo/catalyst_special_projects.html (scroll down the page, to "Past Catalyst Projects"). |

THE BRONX RIVER ALLIANCE AND THE GREENWAY

The Alliance's organizational structure and governance build upon the Working Group's success in actively involving a diverse base of stakeholders in defining and carrying out its mission. The Alliance's organizational and individual partners belong to one or more teams, each of which is responsible for an aspect of the Alliance program. The team structure integrates the involvement of Alliance partners with the day-to-day work of the professional staff. This structure also ensures that values of representation and inclusion are carried into the implementation of our programs. The teams bring together community residents and organizations, educators, scientists, and other professionals, and representatives of the city, state, and federal government agencies.

The Ecology Team defines the principles that guide the Alliance's restoration work. It also serves as a forum to discuss, evaluate, and prioritize environmental studies and on-theground projects, including those carried out by the Alliance's Bronx River Conservation Crew.5

The Bronx River Alliance's Education Program involves youth in water quality monitoring.

The Education Team helps schools and community organizations take advantage of the Bronx River as a rich learning laboratory. The Education Team trains community volunteers as water quality monitors and engages the public in a variety of outdoor educational programs, such as workshops, educational fairs, canoe trips, and student symposia.

The Greenway Team works collaboratively to identify and prioritize greenway projects. The team also serves as a standing community and technical advisory committee and a forum for dialogue about the design and implementation of the greenway.

Each team elects two co-leaders who also serve on the Bronx River Alliance board, giving members an important voice in leading the Alliance and shaping its short- and long-term goals.

In addition to the Ecology, Education, and Greenway Teams, the Alliance's Outreach Program sponsors events and activities to draw people to the Bronx River and to the parks and greenway along its length. The Outreach Program works to develop a broad-based constituency along the river and hosts two annual signature events: the spring Flotilla and the Golden Ball in the fall.

The Alliance staff is headed by an Executive Director who also serves as Parks' Bronx River Administrator. Like other public-private partnerships, the Alliance operates as a not-for-profit organization, but also receives significant in-kind support from NYC Parks. The Alliance staff includes coordinators for each of the four major program areas (Ecology, Education, Greenway, and Outreach), as well as the Bronx River Conservation Crew, a full-time workforce dedicated to maintaining and monitoring the river corridor, and carrying out restoration projects in conjunction with Parks staff.

| 4 | For more about the Bronx River Alliance, see bronxriver.org/whoWeAre.cfm. |

| 5 | The Bronx River Alliance Ecological Principles can be found at bronxriver.org/whatWeDoEcol.cfm#princ. |

The greenway coordinator is the Alliance's principal liaison to the public agencies implementing the many capital projects that are creating the Bronx River Greenway. The $120 million in public funding commitments that the Alliance and its partners have secured since 1999 is allocated to these agencies—chiefly NYC Parks and NYSDOT—and budgeted to the individual projects.

No less significant than the funding commitments are the commitments by the implementing agencies to prioritize the greenway's design and construction, and to work collaboratively to move the greenway forward in a way that reflects the unified vision of a uniquely diverse body of stakeholders. The challenges to realizing the greenway include the realities of limited agency staffing, competing priorities, and genuine differences among public agency standards, protocols, and cultures. The Bronx River Alliance embodies its members' determination to overcome those challenges by facilitating, coordinating, problem solving, and spurring its partners into action.

INTENT OF THE BRONX RIVER GREENWAY PLAN

This plan affirms the collective vision for the Bronx River Greenway and provides a framework to guide its realization. Chapter Two describes the elements of the greenway that are already moving forward and identifies issues that remain to be resolved. Chapter Three discusses guidelines for the incorporation of ecological principles into the greenway's design, construction, and operation (design guidelines to ensure the Bronx River Greenway has a consistent look and feel along its length are included in Appendix I6). Chapter Four describes the Alliance's vision for the greenway's ongoing maintenance and operations. Chapter Five explores ways that new programming can expand the greenway's base of users, enhance their experience, and catalyze revitalization in communities along the river.

The 2002 Tour de Bronx in Soundview Park

| 6 | To download the appendices to this plan, visit www.bronxriver.org/plans. |

The following chapters of the Greenway Plan will:

-

Describe the planned route for the greenway

- Identify greenway projects which are already completed, are in design or construction, or have funding commitments in place.

- Show the responsible agencies and current status for these projects.

- Identify gaps which remain in the proposed greenway route and the issues that need to be resolved in order to fill them.

- Identify on-street routes that connect the greenway to surrounding neighborhoods and important destinations. These routes can serve as interim cycling and walking routes while the greenway is being completed and will provide alternative travel routes for the safety and convenience of users once the greenway is complete.

-

Establish a framework for the implementation of greenway projects that ensures

consistency along the trail and contributes to the ecological revitalization of the river

- Establish design standards and guidelines for greenway elements that will enable the greenway to reflect a unified design vision that responds to the river's varied contexts

- Define Guidelines for Ecological Performance for greenway design, construction, and maintenance to ensure consistency with the Alliance's Ecological Restoration and Management Plan. 7

-

Frame a strategy that will enable the greenway to be maintained over time, emphasizing

the mindful protection of the river

- Identify essential maintenance tasks and the resources required to carry them out, highlighting issues of special concern for river and greenway users

- Consider what organizational structure will best enable the maintenance of the greenway to be coordinated with the work of existing NYC Parks district, borough, and citywide maintenance and operations staff, as well as with the ongoing ecological restoration work of the Bronx River Conservation Crew and NYC Parks' Natural Resources Group

- Anticipate maintenance and operational issues that are likely to arise as new segments of the greenway come into use and identify strategies to address them

- Consider ways that the Alliance can help to ensure that the greenway's maintenance is adequately funded into the future

-

Identify opportunities for new programming that will broaden the base of greenway

users and create economic opportunity for local residents and businesses

- Explore the potential for concessions to contribute economically and programmatically to the greenway

- Identify actions the Alliance can take to encourage concessions that will enhance the greenway and benefit users and residents

- Identify ways that the Alliance can encourage development along and near the river that will enhance the greenway and support the revitalization of the surrounding communities

- Reaffirm the Alliance's commitment to catalyzing development that will benefit rather than displace the low- and moderate-income people who live within the watershed, and identify actions the Alliance can take toward that end

The Bronx River Greenway will transform the lower Bronx River, as well as the communities along its banks. The greenway must therefore embody the Alliance's principles of ecological restoration, environmental justice, inclusion, community ownership, and stewardship. This plan affirms the Bronx River Alliance's commitment both to the restoration of the river, and to the emergence of a vibrant, sustainable, and beautiful watershed that welcomes visitors and offers opportunity to residents.

| 7 | The Ecological Restoration and Management Plan is available at www.bronxriver.org/plans. |

GREENWAY ROUTE: SOUTH TO NORTH • 2

GREENWAY ROUTE FROM SOUTH TO NORTH

The Bronx River Alliance coordinates and tracks the implementation of the New York City portion of the Bronx River Greenway—a continuous bike and pedestrian path that will extend into Westchester County to run the full 23-mile length of the river. The greenway will open up new green space in neighborhoods which now lack it and enhance existing parks. In addition, the greenway will connect neighborhoods currently separated by highways, railroads, and other barriers and provide Bronxites greater access to the borough's many cultural and recreational amenities. The Bronx River Greenway will also be part of the East Coast Greenway—a 3,000 mile-long path that will run from Maine to Florida.1

The Greenway Team—planners, designers, and advocates from the community and government—guides the planning and implementation of the Bronx River Greenway. Our collaborative approach ensures that Bronx residents come to the table with designers and agency representatives in discussing design concepts and implementation priorities for the greenway.

In this chapter, we travel what will be the complete route in the Bronx—from the river's mouth at the East River to the border with Westchester County. Some sections of the greenway— particularly in the north—already exist and require only modest path improvements or the realignment of problem intersections. However, in the South Bronx the greenway is carving out new parkland along the river, creating acres of new green space and access to the waterfront for communities that have long been cut off from the river's banks.

Most of the Bronx River greenway will travel through parkland. However, there are a few segments, especially in the short-term, that will be on-street. Whenever possible, on-street paths will be Class One facilites, meaning that the bike lane is physically separated from motor vehicle traffic. 2

In the following description, the greenway is divided into five segments, according to varying characteristics of the greenway and the different agencies involved in its design and construction. For each segment of the greenway, we describe the route that users will travel, as well as its relevant history and future plans. Connections to other greenways and on-street routes are also identified, to relate the Bronx River Greenway to the City's larger network of bicycle and pedestrian paths, and as a reference for users who may at times prefer on-street routes for security or better connection to their destinations.

The Bronx River Alliance sponsors Pedal and Paddle Day every May to introduce cyclists to the emerging Bronx River Greenway. In 2005, we departed from the Concrete Plant Park.

| 1 | For more information about the East Coast Greenway, visit www.greenway.org. |

| 2 | A description of bike lane classes can be found on Transportation Alternatives website at www.transalt.org/blueprint/chapter4/chapter4b.html. |

From its source to mouth, the Bronx River runs 23 miles, 8 miles of which are in New York City.

SEGMENT A - EAST RIVER TO BRUCKNER BOULEVARD

The southernmost segment of the Bronx River Greenway will include on-street dedicated pathways on both sides of the river to Bruckner Boulevard. One segment of the greenway will run along the east side of the river from Soundview Park; the other originates on the west side of the river at Hunts Point Riverside Park.

East Side of the River - Soundview Park to Bruckner Boulevard

On the east side of the Bronx River, a new greenway path will run from the southeast corner of

Soundview Park along the water to the northwest corner of park (at Colgate and Lafayette

Avenues). From there, the greenway will be a two-way bike and pedestrian pathway along

Colgate, Story, and Bronx River Avenues to the intersection with Bruckner Boulevard.

An alternative route would be made possible by the redevelopment of the Loral site, a vacant industrial property bounded by the river, Story Avenue, Colgate Avenue, and Lafayette Avenue. Rezoning of this site for residential or commercial use would subject future development to the provisions of New York City's Waterfront Zoning regulations, requiring continuous public access along the river. A waterfront pathway along the Loral site would connect Bronx River Avenue directly to the new greenway path in Soundview Park.

SEGMENT A COMPONENT PROJECTS - EAST

|

The New York City Department of Parks & Recreation (NYC Parks) has additional improvements planned for Soundview Park—including lagoon restoration, the creation of active and passive recreational spaces, and an amphitheater. These are among the many Bronx park projects funded under the mitigation agreement established as a condition for the construction of the Croton Filtration Plant in Van Cortlandt Park.

Soundview Park is a former landfill and was closed in the 1960's. Capital projects in the park are encountering delays due to the history of land use on the site. Currently, delays in the park involve difficulty obtaining the necessary permits from the New York State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) to proceed with construction.

Connections to Other Greenways and On-Street Routes

This segment of the Bronx River Greenway makes connections to the following recommended

routes3 listed on the 2006 New York City Cycling Map: Bronx River Avenue, Lafayette Avenue,

and Rosedale Avenue. However, cyclists should be warned that crossing Bruckner

Boulevard on Bronx River Avenue is extremely dangerous, and they should proceed with

caution. Cyclists should use great caution or use the pedestrian bridge over the Bruckner

Expressway at Elder Street.

At the southeastern corner of Soundview Park, the Bronx River Greenway will connect to the Ferry Point Park Greenway, an eight-mile greenway now being developed along the East River waterfront. The Ferry Point Park Greenway will eventually connect to the Hutchinson River Greenway, which via the Pelham Greenway will bring users back to the Bronx River, in a 10- mile loop. The Hutchinson River and Ferry Point Park greenways are currently in development.

An on-street alternative to the greenway for cyclists traveling from the southeast on Leland Avenue to Bronx River Avenue is:

| Left on Patterson Avenue | |

| Right on St. Lawrence Avenue | |

| Left on Lacombe Avenue | |

| Right on Rosedale Avenue | |

| Left on Randall Avenue | |

| Right on Metcalf Avenue | |

| Left on Lafayette Avenue | |

| Right on Colgate Avenue | Left on Story Avenue |

| Right on Bronx River Avenue |

| 3 | According to the map, available at www.nyc.gov/html/dcp/html/bike/cwbm.shtml, recommended routes are streets identified by the New York City Departments of Transportation and City Planning as generally suitable for cycling, but which are not striped or sign-posted. |

SEGMENT A COMPONENT PROJECTS - WEST

|

West Side of the River - Hunts Point Riverside Park to Bruckner Boulevard

The new Hunts Point Riverside Park marks the southern terminus of the Bronx River Greenway

on the west bank of the river. The physical transformation on this site—the former roadbed

of Lafayette Avenue—began in 1997 when community groups developed it as a Green

Street. The mapping of the former street end of Lafayette Avenue as parkland has enabled a

major capital improvement to be carried out in

2004-06 to provide the first new waterfront park in the South Bronx in over

60 years. The completed park will include extensive plantings, as well as a floating

dock, a water play area, a small boat putin site, and an amphitheater. In addition,

the intersection of Lafayette Avenue and Edgewater Road will be striped and

signalized, enabling safer access to the park. Hunts Point Riverside Park abuts

the site of a former fur factory, which is now under construction as a park by The

Point CDC. The Point and Rocking the Boat will utilize the Fur Factory Park's

proximity to Hunts Point Riverside Park and its floating dock to run boating programs

starting in the fall of 2006.

Mayor Michael Bloomberg and Parks Commissioner Adiran Benepe join Majora Carter, Executive Director of Sustainable South Bronx, and Bronx River Alliance Executive Director Linda Cox at the 2004 groundbreaking for Hunts Point Riverside Park.

From Lafayette Avenue, the greenway will proceed north along Edgewater Road. The design of this permanent facility, as well as the configuration of the greenway on the Bruckner Boulevard drawbridge and the crossing of Bruckner Boulevard, will be determined as part of the Bruckner- Sheridan Environmental Impact Study, now being carried out by New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT). Under any of the alternatives being studied—ranging from the construction of a major highway interchange at Bruckner Boulevard and Edgewater Road, to the elimination of the Sheridan and the creation of an elevated interchange at Leggett Avenue— the Bruckner Expressway through lanes will be removed from their current street level. Elevation of the express lanes would allow for major bicycle and pedestrian improvements both along and across Bruckner Boulevard. A Draft EIS is expected in late-2006, and construction is slated to begin in 2011/2012. 4 In the meantime, Congressman Serrano has allocated TEA-21 funds to NYC Parks to develop an interim route for this crucial segment of the greenway.

Until the Bruckner Sheridan interchange is resolved, the nearest point at which it is physically possible to cross Bruckner Boulevard is at its intersection with Bronx River Avenue, on the east side of the river. From Edgewater Road, bikers and pedestrians must travel east to Bronx River Avenue and there cross underneath the Bruckner Expressway. As noted above, cyclists and pedestrians should be aware that this intersection is extremely dangerous and that they should proceed with caution or use the pedestrian bridge over the elevated Bruckner Expressway at Elder Street. From the north Bruckner Service Road, users can double-back over the north side of the drawbridge to reach the Concrete Plant Park (see page 2.6), which is under construction until 2007. Upon the eventual realignment of the Bruckner-Sheridan intersection (scheduled for 2015), this crossing will be much easier; users will be able to cross directly underneath the newly-elevated Bruckner at Edgewater Road to enter the Concrete Plant.

| 4 | Refer to NYSDOT's website for an up-to-date schedule for the Bruckner-Sheridan EIS and construction process: www.dot.state.ny.us/reg/r11/bese/milestones.html. |

Connections to Other Greenways and On-Street Routes

At Lafayette Avenue, the Bronx River Greenway will connect to the planned South Bronx

Greenway, which will run through Hunts Point and Port Morris to Manhattan via Randal's Island.

A planning study for the South Bronx Greenway was completed in 2006, under a contract being

overseen by New York City Economic Development Corporation (EDC). 5

Segment A Outstanding Issues

|

SEGMENT B - BRUCKNER BOULEVARD TO EAST TREMONT AVENUE

The Concrete Plant Park

From Bruckner Boulevard, the greenway route proceeds north through the city-owned site known

as the Concrete Plant Park. This site has a storied past; suspected as having ties to organized

crime, the plant went bankrupt in 1987 after the owner was convicted on price-fixing charges.

The site was then acquired by the City of New York and put up for public auction. However, in

response to community pressure the City withdrew it from public auction in 1999 and agreed to

set it aside as parkland.

| 5 | For more information about the South Bronx Greenway, see Sustainable South Bronx's website at www.ssbx.org/greenway.html. |

The Concrete Plant Park has been used as a public park since 2000, when control of the site was transferred to NYC Parks. During this time, a temporary, bark-mulched pathway was constructed by volunteers to lead down the steep slope from Bruckner Boulevard, to connect to an extensive, concrete-paved area and the mapped, but unimproved section of Edgewater Road that exits the site to the north at Westchester Avenue. The Concrete Plant was also used to house a native plant nursery used by Parks Natural Resources Group (NRG) to provide plant stock for ecological restoration throughout the Bronx. In addition, the Alliance and its partners used boats stored in containers on the site for events and activities.

SEGMENT B COMPONENT PROJECTS

|

Construction of the Concrete Plant Park will be implemented over several phases. Beginning in the summer of 2005, the first phase began with selective demolition of several structures. Some of the steel structures surviving as remnants of the former concrete batching operation will be stabilized and retained as sculptural elements of the site. In future phases, they may be used to support wind turbines and solar panels to provide energy for park buildings and lighting, funded through the mitigation of the Croton water filtration plant in Van Cortlandt Park.

January 2005 view of the Concrete Plant Park from the south.

Following demolition, the next phase of the Concrete Plant Park's development will create a number of improvements, including a continuous greenway, a waterfront promenade, new plantings, small boat access, space for cookouts and outdoor performances, an improved connection to Bruckner Boulevard, and additional restoration of shoreline vegetation.

However, design for the area of the park west of Edgewater Road cannot be completed until the Bruckner-Sheridan EIS is finished in 2007, since all of the alternatives under consideration for the Bruckner-Sheridan Interchange would have important impacts on this site. In addition, full build-out of the Concrete Plant Park cannot take place until the reconstruction of the Bruckner- Sheridan Interchange is completed (projected 2015), since a portion of the site is proposed to be used for construction access and staging.

Adjacent to the Concrete Plant Park is a vacant railroad station designed in 1910-11 by the legendary architect Cass Gilbert for the New York, New Haven & Hartford Rail Road. The station stands directly west of the site's exit at Westchester Avenue above what are now Amtrak's North East Corridor tracks. Youth Ministries for Peace and Justice conducted a building assessment and lead a community visioning process for the structure in 2005. YMPJ is now studying the feasibility of restoring the station building for a use that would serve as a community gateway to the Concrete Plant Park.

View of the Cass Gilbert station from the Concrete Plant Park.

Westchester Avenue to East Tremont Avenue

From Westchester Avenue to East Tremont Avenue, the Bronx River Greenway is being

implemented by NYSDOT, with coordination with NYC Parks and the Bronx River Alliance.

Basemap courtesy of NYSDOT.

Westchester Avenue At-Grade Crossing

A signalized, mid-block crossing is planned where the greenway exits the Concrete Plant, to

mitigate hazards to cyclists and pedestrians created by vehicle traffic on Westchester Avenue,

particularly vehicles turning onto and off from the nearby ramps to the Sheridan Expressway.

PDJ Simone Impound and Apex Auto sites

After crossing Westchester Avenue, the greenway will enter a site that is now privately

owned, and will be acquired by NYSDOT to enable the development of a continuous,

waterfront pathway. The PDJ Simone impound lot is now used to store vehicles seized

by federal marshalls. NYSDOT plans to demolish the buildings, regrade the site, and

remediate any environmental contamination. Concrete blocks previously used to

stabilize the shoreline will be removed, and the river bank will be restored to a natural

vegetated slope.

View of PDJ Simone and Apex properties from Westchester Avenue, looking north—before greenway construction (photo from NYSDOT)

View of PDJ Simone and Apex properties from Westchester Avenue, looking north—after greenway construction (photo from NYSDOT)

The pathway will cross the river on a new, prefabricated steel truss bridge to access the parcel currently occupied by Apex Auto, an auto salvage operation. This site is over 600 feet long, but has only two, widely separated 20-foot segments of street frontage. The remainder of the site is a long sliver of land bounded by Amtrak to the west, and a row of attached residential buildings to the east on Bronx River Avenue.

The greenway will exit the north end of the Apex Auto site at East 172nd Street, turn west onto a new bridge above the Amtrak line, and descend via several switchbacks to near river level. Here the pathway will branch, offering users two options. One is to continue along the east bank of the river, on now-undeveloped land owned by NYC Parks. The other is to cross a third new bridge and enter Starlight Park on the west bank. The two paths re-connect over a fourth new bridge north of Starlight Park to form a one-kilometer loop along the river.

Starlight Park

Starlight Park was developed in the 1960's, in conjunction with the construction of the Sheridan

Expressway. A private amusement park of the same name was condemned by Robert Moses

for the Sheridan right-of-way; the present Starlight Park was constructed as a replacement.

Though the surrounding communities suffer from a lack of open space and recreational facilities,

Starlight Park was poorly utilized due to its poor condition, outdated recreational facilities, and

difficulty of access.

An agreement negotiated in 2001 between NYSDOT and NYC Parks permitted the utilization of Starlight Park as a staging area for the reconstruction of the Sheridan Expressway by NYSDOT. This agreement also provided for the installation of an upgraded stormwater collection and treatment system for runoff from the Sheridan underneath the park. In exchange, NYSDOT committed funds for a major reconstruction and upgrade of the park, and assigned its landscape architects to work closely with local residents on the redesign.

When the construction of the drainage system began in 2003, high levels of contamination were found in the excavated soil, and it was discovered that the site formerly housed a manufactured gas plant, operated by a predecessor company to Con Edison. Work was halted while Con Edison negotiated a cleanup agreement with DEC. A Remedial Action Work Plan was approved in 2004, and remedial work, including removal and safe disposal of the contaminated soil, will be carried out in 2006/07. Completion of the remedial work will allow the reconstruction of Starlight Park to move forward in 2007, with completion projected in 2009.

The reconstructed park will include a continuous pathway along the river (the river was completely fenced off in the former park configuration). A comfort station and boat storage building will also be constructed in latter phases by NYC Parks, with funding provided by Congressman Serrano. Funds from the mitigation funds from the Croton Filtration Plant will enable Parks to expand on the boat storage building, to provide space for community events and environmental programming, and for the headquarters of the Bronx River Alliance itself—all at the south end of Starlight Park. The Rebuild / Renew NY Transportation Bond which passed in November 2005 will fund a floating dock to enable small boat users to launch and cross the 172nd Street weir even at low tide.

Starlight Park to East Tremont Avenue

North of Starlight Park, the greenway crosses below the Cross-Bronx Expressway and

enters land that will become parkland under an agreement between Parks, NYSDOT,

the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), and the Metropolitan

Transit Authority (MTA).

North of the Cross-Bronx Expressway, NYSDOT plans to reconfigure the intersection of E. 177th Street, Devoe Avenue, and E. Tremont Avenue, at the entrance to the MTA bus depot. The new design significantly greens the street, improves safety, and calms traffic at what is currently a confusing and hazardous location. In addition, the parcel of land bounded by those streets will be converted from an illegal parking lot into a park and a natural, vegetated slope down to the river will be restored. On the opposite bank of the river at this location is Drew Gardens, a 2-acre botanical and vegetable garden was developed in 1995 by the Phipps Community Development Corporation.

Drew Gardens on the Bronx River.

The greenway will cross E. Tremont Avenue at a signalized mid-block crossing, bringing users to Bronx Street.

Connections to Other Greenways and On-Street Routes

This segment of the Bronx River Greenway connects to Bronx River Avenue, which

north of the Bruckner Expressway is a recommended route listed on the 2006 New

York City Cycling Map.

The on-street detour for cyclists, pedestrians, and rollerbladers traveling from the Concrete Plant Park at Westchester Avenue and who wish to connect to E. Tremont Avenue is the following:

| At the intersection with Whitlock Avenue, cross Westchester Avenue | |

| Right onto Home Street | |

| At the triangle, bear right onto West Farms Road | |

| Right onto E. Tremont Avenue |

Segment B Outstanding Issues

|

SEGMENT C - EAST TREMONT AVENUE TO PELHAM PARKWAY

|

|

West Farms

The West Farms segment of the greenway runs along what is currently one of the most accessible sections

of the river in the South Bronx. Here the river is fastflowing, and greenway users can see the "Bronx River

Rapids"—one of the most exciting sections of the river to canoe.

SEGMENT C COMPONENT PROJECTS

|

At the intersection of Bronx Street and E. Tremont Avenue is the Bronx River Arts Center (BRAC), a multiarts organization dedicated to providing art and environmental programming for residents of the Bronx. Improvements at BRAC—including a terraced patio leading down to the river—will create an enhanced public outdoor space along this section of the greenway.

Canoeing the "Bronx River Rapids" in West Farms

Beyond BRAC, the greenway continues north on the west bank of the river and utilizes the streetbed of Bronx Street, which is now closed to motorized vehicle traffic. Bronx Street is just one block long and terminates at E. 179th Street. From there, the greenway will continue north along a narrow strip of parkland behind the Lambert Houses to 180th Street. An agreement with Phipps Housing, Inc., the nonprofit owner and manager of the Lambert Houses, would allow for a wider, straighter path alignment and better access into and out of this greenway segment via bicycle. This agreement would also provide improved lighting and security.

In 2007, NYC Parks will begin construction on a capital prjoect that will open up sight lines and improve safety along this greenway segment. New features will include a butterfly garden, a canoe put-in, lighting, game tables, and bike racks.

At E. 180th Street, the path emerges directly opposite from River Park. River Park's rock outcroppings overlook the 20-foot high waterfall where the river exits the Bronx Zoo. Parks received $900,000 from the Croton mitigation funds to make improvements to River Park, including reconstructing the playground, comfort station, and picnic area located adjacent to the greenway. Construction is scheduled to begin late summer/early fall 2006.

Canoeing the "Bronx River Rapids" in West Farms

East 180th Street to Bronx Park East

The greenway path alignment from 180th Street to Ranaqua (Bronx Borough Headquarters of

NYC Parks) and Bronx Park East has not yet been determined. This area's complex topography

and many layers of rail, street, and highway infrastructure create real challenges to the

development of a safe and inviting route. A promising alternative would create a Class One

pathway along the north side of E. 180th Street, which could connect to new pathway between

the MTA and Fire Department properties. The path could then run along the edge of a Zoo

maintenance and storage area and under the Bronx River Parkway. From there the path could

run adjacent to Ranaqua's vehicle storage yards. This option would involve minimal elevation

change for the pathway, but rights-of-way would have to be worked out with the Bronx Zoo, the

MTA, NYC Parks, and potentially the NYC Fire Department.

This route will bring the path onto Ranaqua. The complex serves as the Borough Headquarters for Parks and houses administrative, operations, program offices, maintenance and repair shops, and facilities for vehicle storage and maintenance.

Traffic exiting and entering the northbound Bronx River Parkway from Ranaqua's driveways and parking lots has been a hazard to pedestrians and cyclists. A path alignment can be developed that will minimize conflicts, but it may be desirable to curtail use of the driveways by through traffic. New signage and barricades installed in late spring of 2005 have already dramatically reduced unauthorized traffic through the Ranaqua property and improved safety in the complex.

Whether the greenway path should run in front of or behind Ranaqua remains to be determined. Trade-offs include maximinzing the greenway's visibility, minimizing conflicts with vehicular traffic, maintaining necesary parking spaces, and minimizing impact on landscaped areas.

The most likely route for the greenway will exit Ranaqua to the north along the NYC Parks employee parking lot. From there, the greenway will enter a forested section of Bronx Park East, and connect with existing park paths, which will be improved and marked as part of the greenway path.

Proposed Bronx River Parkway Viaduct Spur Path

NYSDOT is planning a number of major projects on the Bronx River Parkway. As a part of

improving vehicular conditions on the Parkway, NYSDOT also plans to develop a separated

bike path on the viaduct between the Noble Playground (just north of the Cross Bronx

Expressway) and Ranaqua.

Connection to Bronx Zoo River Walk / Pelham Parkway Intersection

From Bronx Park East, the path will cross Boston Road, which provides access to the Bronx

Zoo's eastern parking lot and entrance. A planned NYSDOT project is to reconfigure the

intersection of Boston Road, the Bronx River Parkway entrance and exit ramps, and Pelham

Parkway. This project has received partial funding—$2 million—through SAFETEA-LU,6 which

will enable planning and feasibility studies. The reconfiguration of this intersection would provide

an opportunity to integrate the design of the greenway with the road and ramp system here.

The Riverwalk includes interpretive signage and an overlook of the Bronx River.

Continuing north on the greenway, users must cross Pelham Parkway, which will be realigned by the NYSDOT "Zoo Access" project mentioned above. Currently, pedestrians and cyclists are directed by signs to travel to the east side of the intersection. From here, they must then backtrack on the north sidewalk of Pelham Parkway, and re-enter the greenway after crossing the access ramp between Bronx Park East and the northbound Bronx River Parkway.

Connections to Other Greenways and On-Street Routes

This segment of the Bronx River Greenway makes connections to E. 180th Street, Morris Park

Avenue, White Plains Road, Bronxdale Avenue, Rhinelander, and Bronx Park East—all

recommended routes listed on the 2006 New York City Cycling Map. In addition, this segment

connects to the forthcoming Bronx River Parkway Viaduct Greenway at Ranaqua and to the

Mosholu-Pelham Greenway at Pelham Parkway, a popular route providing access to Orchard

Beach, City Island, and the Shore Road bike path.

| 6 | SAFETEA-LU is the Safe, Accountable, Flexible, Efficient Transportation Equity Act: A Legacy for Users, the federal transportation bill authorized in August 2005. For more information about SAFETEA-LU, see www.fhwa.dot.gov/safetealu/. |

The on-street detour for cyclists, pedestrians, and rollerbladers traveling from E. Tremont Avenue and who wish to connect to Pelham Parkway is the following:

| Turn north onto Boston Road | |

| Right onto E. 180th Street | |

| Left onto Morris Park Avenue | |

| Left onto Amethyst | |

| Left onto Sagamore (under the elevated train tracks) | |

| Right onto Unionport | |

| Left onto Bronx Park East to the intersection with Pelham Parkway |

Segment C Outstanding Issues

|

SEGMENT D - PELHAM PARKWAY TO EAST 211TH STREET

Allerton Avenue / Kazimiroff Boulevard Intersection

North of the intersection with Pelham Parkway, the greenway will utilize improved, existing park

paths through the portion of Bronx Park lying between Bronx Park East and the Bronx River

Parkway. These paths were marked with pavement markings denoting pedestrian and bike use in 2004.

SEGMENT D COMPONENT PROJECTS

|

At Allerton Avenue, the greenway encounters another problematic ramp crossing. Currently, non-motorized users have difficulty crossing this intersection because of the high volume of traffic traveling at high speeds and making turns onto and off of the Bronx River Parkway. This conflict could be mitigated by improving sight lines, and by adding a lengthened "pedestrians-only" phase to the traffic signal here. NYSDOT has plans to realign this intersection as a part of improvements to the Bronx River Parkway. These plans have a 2007 start date and could include adding a new traffic signal at the intersection of Allerton and Bronx Park East, with a dedicated phase for pedestrians, cyclists, and rollerbladers. This proposal also involves three additional traffic signals—each with a phase dedicated to non-motorized travelers. Two would be located at the on- and offramps on the east side of the Bronx River Parkway and Kazimiroff Boulevard. The other would be located west of the Parkway (also on Kazimiroff Boulevard). All of these improvements—

which include widening the shared sidewalk and path on the north side of Kazimiroff—would enhance the connection of the Bronx River Greenway to the Mosholu-Pelham Greenway, as well as allowing Bronx River Greenway users to continue north/south. As of mid-2006, proposals and designs are still being evaluated for this intersection.

Bronx Park East

North of the intersection with Allerton Avenue, the main greenway path continues north and

runs along the east side of the Bronx River Parkway and the river.

Spur Loop Path

Bronx Park North Bikeways: French Charley, Allerton / McCarthy-Cunnion-Hourigan Ball Fields

Although this is not the main section of the greenway, this spur connects to the Mosholu

Greenway to the west and makes a loop between Allerton and Burke Avenues. After traveling

west along Kazimiroff Boulevard but before the Botanical Gardens Metro North station, the path

makes a sharp turn north and enters a popular park with several ballfields, a comfort station,

and a playground. The area around the ballfields has many colorful names, including the French

Charley playground, named after Charley Mangin who owned a nearby French restaurant in the

1890s. His establishment, in the heart of a small French enclave of the Bronx, was popularly

referred to as French Charley's. The ballfields in the area are also frequently referred to as the

Allerton ballfields. However, the true name of these athletic fields is the McCarthy-Cunnion-

Hourigan fields, named after three local residents who were killed in action in Vietnam.

The section of the greenway path that runs along Kazimiroff Boulevard, the ballfields, and playground will be repaved and striped in 2006/07.

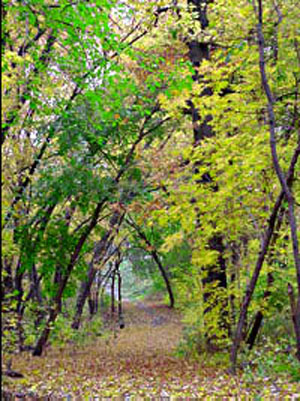

Bronx River Forest

Beyond French Charley, the path enters the Bronx River Forest, where a $3 million floodplain

restoration project was completed in June 2005. The path here follows the old roadbed of the

Bronx River Parkway to Burke Bridge—a newly-renovated scenic look-out complete with new

signage, bollards, and benches. Paved has been reduced significantly, from the 40-foot wide

roadbed of the former parkway, to the 16-foot width required to serve pedestrians and bicyclists.

The main greenway path will not enter the restored area, where invasive plants species have been

replaced with natives and the ecological function of the floodplain has been improved. Pedestrian paths

and boardwalks from the Burke Bridge, however, provide access along the waterfront, and interpretive

signs will explain how the restored forest contributes to the health of the river. Leaving the Bronx River

Forest via the Burke Bridge, the path then runs beneath a low, stone-faced Bronx River Parkway

overpass and reconnects with the primary greenway path east of the Parkway.

View of the Bronx River from the Burke Bridge

Main Greenway Path, Burke Avenue to Gun Hill Road

The main greenway route continues north from Burke Avenue along improved park paths to Magenta Street. From Magenta

to East 211th Street, the greenway will either utilize one lane of Bronx Boulevard, another segment of the original Bronx

River Parkway, or a widened sidewalk which will be marked as a shared use facility. The Alliance is coordinating

communication between NYC Park and NYC DOT about the alignment of this path. As the greenway passes under the

brick-arched viaduct of Gun Hill Road, a narrow pathway at the river level can be accessed from a stairway at Duncomb

Avenue in the center of Bronx Boulevard. This soft path allows users to enjoy the Duncomb bridge arches, reflected in the

slow-moving river and also connects back to the pedestrian paths in the Bronx River Forest.

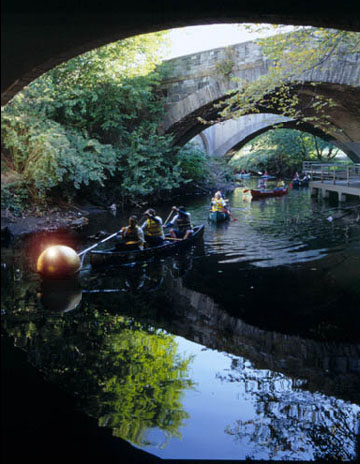

Golden Ball passes underneath the Duncomb Bridges

Connections to Other Greenways and On-Street Routes

This segment of the Bronx River Greenway makes connections to Allerton Avenue, Burke Avenue,

and Webster Avenue—all recommended routes listed on the 2006 New York City Cycling Map.

(However, please note that Mace Avenue may be preferable to biking on the very busy Allerton

Avenue.) In addition, at Pelham Parkway and Kazimiroff Boulevard, the Bronx River Greenway

connects to the Mosholu-Pelham Greenway system.

Cyclists, rollerbladers, and pedestrians will likely feel fairly safe on this segment of the greenway, due to its close proximity to street activity. However, in the case that they do not or need to travel to a destination not directly along the greenway, we recommend that they travel on Bronx Park East—a wide and sparsely-traveled road—even though it is not listed as a recommended route on the NYC Cycling Map.

Segment D Outstanding Issues

|

SEGMENT E - EAST 211TH STREET TO THE CITY LINE

North of Gun Hill Road, a new entrance at 211th Street will identify both the greenway and Shoelace Park—the narrow strip of parkland that runs from 211th Street to 228th Street. The improved multi-use path will follow the existing upper-level asphalt path along the old Bronx River Parkway. The narrower existing pedestrian path near the river level allows access to the river and canoe put-in at 219th Street. Another improved entrance at 219th Street will reinforce the identity of the park and its connections to surrounding neighborhoods. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is currently studying ways to minimize stormwater run-off in this badly eroded park and plans to implement a demonstration project here. Their findings will be incorporated into the final design for the improvements to Shoelace Park.

SEGMENT E COMPONENT PROJECTS

|

From 226th to 233rd Street, the divided roadway of Bronx Boulevard is now used by cyclists, joggers, and walkers and could accommodate the greenway path. However, the ramp access to the north bound Bronx River Parkway is a major hazard here, as is the at-grade crossing of East 233rd Street, where there is no crosswalk, and where the existing traffic signal provides no phase during which pedestrians or cyclists can safely cross.

For safety reasons, the proposed permanent greenway route will instead:

| Cross the river and the Parkway on a new pedestrian / bike bridge; | |

| Cross below the Metro North tracks on the west bank on an improved existing path at the 233rd Street / southbound Parkway ramp; | |

| Cross below east 233rd Street using the existing underpass of the Parkway ramp / service road |

This alignment would eliminate several significant hazards, and bring users to the Webster Avenue on-street greenway that will ultimately connect to the Westchester County (on-street) bike route. Developed this way, the greenway will also provide access on the west bank of the river to the unique area known as Muskrat Cove.

Muskrat Cove

Parkland directly north of the Woodlawn Metro North parking lot is called Muskrat Cove for the

population of muskrats that are sometimes seen on the river, particularly around dusk. This

little-known park is now accessible by a deteriorated paved path through an opening in a

guardrail. It provides an intimate experience of the river, and shelters diverse animal and plant

life. A narrow walkway now runs along the river, far below the arched viaducts of the Bronx

River Parkway and Nereid Avenue.

A NYC Parks capital project will begin construction in late 2006/early 2007. Once complete, the greenway will enter Muskrat Cove through a new entry plaza and seating area that will draw attention to this gateway at the Metro North Woodlawn Station. The greenway here will be an 8- foot wide path on the west bank of the river, and will terminate about 6/10 of a mile in at a scenic pedestrian bridge, where Westchester County's on-river path will eventually connect to ours. Crossing this bridge, users will be able to follow an earthen path on the eastern bank of the river. Depending on NYSDOT's alteration of the Bronx River Parkway, a path will lead back up onto Bullard Avenue and the Bronx River Parkway, enabling users to loop back to the west bank of the river on a trail that would be slightly under a mile in length and enhanced with interpretive signage.

Path in Muskrat Cove

On-Street Connection to Westchester County

An on-street greenway route along Webster Avenue will connect to the Westchester County

portion of the Bronx River Greenway. Webster Avenue becomes Bronx River Road at the City

Line, 238th Street / Nereid Avenue. North of the line, the City of Yonkers plans to continue a

marked, on-street connection to the existing Bronx River path in Mount Vernon. From this point,

the path continues, with a few interruptions, to Kensico Reservoir, where the headwaters of the

Bronx River are impounded.

Connections to Other Greenways and On-street Routes

This segment of the Bronx River Greenway makes connections to Webster Avenue, E. 228th

Street, E. 229th Street, and Nereid Avenue—all recommended routes listed on the 2006 New

York City Cycling Map. 222nd Street is an excellent east/west biking route that is not listed on

the Cycling Map.

The on-street detour for cyclists, pedestrians, and rollerbladers traveling through this area is Webster Avenue for those who are west of the river and Bronx Boulevard for those east of the river.

Segment E Outstanding Issues

|

GUIDELINES FOR ECOLOGICAL PERFORMANCE • 3

CHAPTER 3: GUIDELINES FOR ECOLOGICAL PERFORMANCE: DESIGN, CONSTRUCTION, AND MANAGEMENT

The ecological performance guidelines presented in this chapter are a vision for the design, construction, and maintenance of the Bronx River Greenway that will restore the river as the heart of a living ecosystem. In their totality, these practices operationalize one of the Bronx River Alliance's fundamental principles—that the creation of the Bronx River Greenway positively contribute to the health of the Bronx River. At a minimum this means avoiding negative impacts where possible and minimizing them when unavoidable. But beyond mere impact avoidance, decades of community activism and community participation in the revitalization of the Bronx River have led to a vision of the Bronx River Greenway that is both an ecological restoration project and a recreational amenity. The Alliance and the public agencies that are implementing the greenway—principally New York City Department of Parks & Recreation and New York State Department of Transportation—are working to ensure that the millions of dollars invested in creating the greenway will also advance the river's recovery. This chapter outlines the principles that will guide this work.

The Ecological Performance Guildelines presented in this chapter offer ways for the Bronx River Greenway to contribute to the ecological revitalization of the river.

These principles build upon the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation's evolving body of knowledge and practice, especially the work of the Natural Resources Group (NRG), which has been a long-standing and active member of our the Bronx River Alliance's Ecology Team. Yet, the integration of the greenway and its central ecological asset—the Bronx River— requires a framework that embraces both ecological and recreational values. By articulating a set of principles based on those values, the Bronx River Greenway can be a new model of park development, accommodating both active use and ecological restoration.

Putting those principles into practices will reveal some inherent challenges, some of which are examined in this chapter and the next. How do we provide vegetated landscapes while maintaining open sight lines for security? How do we strike the right balance between recreational uses and ecological restoration of the river? These questions cannot be answered out of context; they require site-specific consideration. This chapter is the first step toward establishing a framework within which such competing values can be evaluated and reconciled.

Finally, these practices should not remain rigid over time, but rather require continuous reflection, evaluation, and modification to incorporate new knowledge and experience into future decisions.The following ecological performance guidelines were developed by Mathews-Nielsen Landscape Architects, and draw upon the expertise of the Bronx River Alliance Greenway and Ecology Teams, as well as Mathews Nielsen's own depth of experience. These practices are broken out into the following categories: landscape, stormwater management, hardscape, streetscape, and sustainable maintenance practices, although there is significant overlap among these areas (e.g., vegetated landscapes promote stormwater capture).

I. LANDSCAPE

The landscape practices presented here emphasize the importance of maintaining healthy soils,

avoiding negative impacts to sensitive areas, and strengthening natural landscape features,

especially wetlands and floodplains. This section also addresses appropriate vegetation along

the greenway.

LANDSCAPE GOALS

|

Landscape Best Management Practices

ACKNOWLEDGE SOIL AS A LIVING SYSTEM; PERFORM SOIL ANALYSIS AND ASSESSMENT

- Monitor and learn from local soil conditions

- Retain native soils that are relatively undisturbed

- Use structural soils to increase longevity of trees and adjacent pavements

- Design soils at paved areas to provide load-bearing capacity for pavements as well as nutritional components

DEVELOPMENT OF SITE PROTECTION PLANS TO PROTECT SENSITIVE AREAS

- Protect existing habitats by developing clear landscape protection plans and specifications

- Identify requirements for hand excavation, root pruning, and transplanting

- Protect native soils and future planting areas from compaction and contamination during construction

A recent project in the Bronx River Forest simultaneously improved greenway paths and restored the river's floodplain.

STRENGTHEN NATURAL SITE PATTERNS

- Preserve and restore riparian corridors and wetlands by creating buffers

- Include floodplain areas in the riparian buffer for maximum wildlife benefit

- Align pathways and locate improvements with consideration of the river environment

A Bronx River Conservation Crew member tackles Japanese Knotweed, an invasive species on the Bronx River.

ENHANCE NATIVE HABITAT AND GENETIC DIVERSITY

- Design landscapes based on principles of ecological succession, selecting appropriate, low maintenance native plants (see Appendix III for a list of plants native to the Bronx River watershed). 1

- Remove invasive plants to avoid habitat degradation, particularly at edge conditions

- Design to encourage diversity of vegetation and to reinforce edge conditions

| 1 | Appendices for the Bronx RIver Greenway Plan are available at www.bronxriver.org/plans. |

MAXIMIZE BENEFITS FROM TREES

- Plant trees to maximize pavement shading and reduce heat island effect

- Plant trees in connected soil zones

- Plant smaller caliper trees and whips for greater success rates

II. STORMWATER MANAGEMENT

A primary goal for the Bronx River Ecological Restoration and Management Plan is to improve

stormwater capture to reduce the number of combined sewer overflow (CSO) events and

contribute to the goal of a fishable and swimmable Bronx River. The integration of infiltration

basins, bioretention ponds, and other features into the design of greenway sites will make real

contributions to the health of the river; however a more comprehensive watershed-wide approach

will be required to have a significant impact on CSO events. 2 Integrating the following practices

into the construction of the greenway, however, will make important progress toward the level

of stormwater capture necessary to reduce CSO events.

STORMWATER MANAGEMENT GOALS

|

Stormwater Best Management Practices

RESPECT NATURAL DRAINAGE PATTERNS AND USE STORMWATER AS AN ASSET AND NOT AS A WASTE

- Develop methods for stormwater management based on the site's location within the watershed and floodplain systems

- Provide erosion control or prevention measures at the source to reduce downstream impacts

- Provide temporary erosion control measures on partially completed projects or if soil is to remain exposed for more than 30 days

- Design for water conservation by grouping plants with similar water requirements; consider rainwater harvesting systems and water conserving irrigation systems

Volunteers lay bio-fabric along the Bronx RIver's shores in Shoelace Park to prevent bank erosion. |

An upland erosion-control project in Shoelace Park stabilizes the slope down to the river. |

| 2 | See the Bronx River Ecological Restoration and Management Plan for a more detailed discussion of stormwater management goals: www.bronxriver.org/plans. |

The 211th and 219th Street entrances to Shoelace Park offer an opportunity to reduce impervious surfaces, and promote retention and infiltration of stormwater near the Bronx River.

DESIGN SITES TO MAINTAIN OR RESTORE BENEFICIAL DRAINAGE PATTERNS

- Minimize paved areas

- Maximize porous and permeable surfaces

USE INFRILTRATION AND FILTRATION PRACTICES

- Use infiltration trenches to slow run-off and allow infiltration to occur

- Use bio-retention areas (shallow, landscaped depressions) to provide on-site treatment of stormwater run-off

- Support the development of green roofs, and the reduction of paved surface area within the Bronx River watershed

USE DETENTION AND RETENTION PRACTICES

- Use shallow wetlands to treat stormwater run-off, incorporating permanent pools and/or extended detention storage where feasible

III. HARDSCAPE

The construction of a multi-use path unavoidably incorporates some hardscape. However, we

can control the placement, materials used, and hierarchy of paths to minimize impact on the

river. Paths can also be built to reflect how users will interact with the space (i.e., along "desire

lines"), minimizing off-trail use and associated erosion.

HARDSCAPE GOALS

|

Hardscape Best Management Practices

CREATE HIERARCHY OF PATHWAYS FROM RIVER TO UPLAND AREAS BASED ON ECOSYSTEM AND PROGRAM NEEDS

- Pathways near river to be made of porous materials or to provide run-off detention system

- Encourage compact development and increased path connectivity to reduce number of access routes

- Provide well-designed access points and wayfinding system to keep people on the greenway trails 3

The reconstruction of the pedestrian pathway by the river in Shoelace Park is an opportunity to integrate stormwater management practices, such as infiltration trenches or pervious pavement.

MINIMIZE PAVED AREAS TO REDUCE RUN-OFF AND MITIGATE URBAN HEAT ISLAND EFFECT

- Use minimum pavement widths near the river, where feasible

SELECT PATHWAY ALIGNMENTS AND PAVEMENT MATERIALS WITH AN UNDERSTANDING OF BOTH USER SAFETY AND CONSTRUCTION IMPACTS

- Use previously disturbed areas and existing base courses wherever possible to minimize site disturbance

- Consider pedestrian and bicycle safety, as well as hydraulic efficiency, when locating stormwater inlets

IV. STREETSCAPE

These streetscape best practices address the use of long-lasting, high-efficiency lighting,

reducing reflectivity of surfaces, and implementing stormwater management practices in road

and parking lot construction.

STREETSCAPE GOALS

|

Streetscape Best Management Practices

SELECT LIGHTING STANDARDS FOR LONG TERM ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFIT AND SAFETY

- Use lamps with high luminaire efficiency

- Use long-lasting luminaries in sensitive areas to reduce site disturbance and vehicular traffic

- Improve reliability by using photovoltaic street lighting

- Reduce light pollution (refer to IESNA Recommended Practice Manual) 4

| 3 | The Bronx River Alliance has contracted with Donna Walcavage Landscape Architects and Urban Design to develop a signage master plan for the Bronx River Greenway. The signage plan will be complete by fall 2006. |

SELECT MATERIALS TO REDUCE HEAT ISLAND EFFECT

- Provide shade on at least 30% of non-roof impervious surfaces within five years of new construction

- Use light-colored/high albedo materials for non-roof impervious surfaces where feasible

DESIGN ROADWAYS AND PARKING LOTS TO FACILITATE ON-SITE STORMWATER MANAGEMENT

- Use low-lying intersections or medians for bio-retention

- Develop roadway shoulder treatments that provide infiltration

- Reduce or eliminate use of pesticides and salt in roadway maintenance

New curb "bulb outs" in front of the Bronx River Art Center will provide a safer crossing of E. Tremont Avenue, green the street, and promote stormwater capture.

V. SUSTAINABLE MAINTENANCE

Maintenance and operations will play a large role in defining the ecological footprint of the

greenway. These practices outline how to keep the health of the river in mind while controlling

pests, managing wastes, and conducting routine maintenance of green space.

MAINTENANCE GOALS

|

Greenway Maintenance Best Management Practices

USING BIO-INTENSIVE INTEGRATED PEST MANAGEMENT (B-IPM)

- Minimize use of synthetic chemicals

- Specify pest resistant cultivars

- Specify a diversity of appropriate plant species

- Establish thresholds of acceptable appearance levels in landscape areas

- Monitor plantings monthly for health and control of invasive species

UNDERSTAND THE LIFE CYCLES OF MATERIALS PRIOR TO SELECTION

- Recognize lifespan and regeneration of proposed materials and balance with associated costs

- Consider intensity of use and site constraints (flooding)

IMPLEMENT RECYCLING AND COMPOSTING PROGRAMS

- Increase use of recycled materials in pavement sections

- Provide recycling containers in Bronx River parks

- Create on-site composting and mulch piles and use it to improve local soil conditions. Or obtain compost from local municipal facilities for application along the river.

SCHEDULE MAINTENANCE PROGRAM TO RESPOND TO SITE SPECIFIC REQUIREMENTS

- Operate equipment in sensitive landscape areas when soils are dry enough to support equipment

- Use low ground pressure equipment, such as wide tire or tracked equipment, to minimize impact

- Conduct activities in wetlands on firm or frozen ground that can support equipment to avoid rutting

Volunteers at Drew Gardens use a 3-bin compost system to transform garden clippings into compost. This project offers a model for how to implement and maintain compost facilities in other locations along the Bronx River Greenway.

MAINTENANCE AND OPERATIONS • 4

The realization of the Bronx River Greenway is a magnificent achievement, made possible by years of creative collaboration among Bronx River Alliance's partners, especially the New York City Department of Parks & Recreation. The completion of each successive greenway segment creates a new asset that will yield ecological, social, and economic benefits for years to come. These assets also require mindful stewardship and a commitment of resources going forward if they are to continue to enrich the river, its watershed, and the communities along its banks.

This section of the Greenway Plan outlines the specific tasks that maintaining the greenway will entail, identifies the staffing and resources needed to accomplish them, and highlights the special challenges of carrying forward the vision for operating the greenway that has emerged from years of community-based planning and consensus building. Finally, this chapter explores strategies for funding this work and ensuring that the unparalleled accomplishment that the greenway represents will not only endure, but will become more beautiful, sustainable, and alive with each passing year.

STRUCTURE, STAFFING, & SCOPE OF ROUTINE MAINTENANCE

Structure and Staffing

The completion of the greenway will effectively create a new linear park traversing several

existing NYC Park districts. Once projects creating major contiguous greenway segments are

completed, a new Bronx River Greenway district will be created to facilitate consistent

maintenance end-to-end (especially of pathways). In addition, a consolidated Bronx River district

will enable coordination of regular maintenance practices with ecological restoration work, and

the identification of dedicated funding sources to help underwrite the greenway's maintenance

costs. Initial staffing could be small, growing as additional greenway segments open for use.

Staffing Levels and Supervisory Structure

A supervisor and crew would be responsible for tasks that are identified as "district-based".

Scope of Routine Maintenance

Routine maintenance of the greenway will include the tasks that are common to all of the City's

parks and greenways. Some tasks are seasonal or will vary seasonally in the effort they demand.

NYC Parks training for maintenance staff supports a holistic approach to maintenance within

geographically-defined zones and enables a district-based crew to be responsible for all routine

maintenance tasks, including cleaning, minor repairs, and care of plantings.

Daily greenway maintenance tasks will be carried out by district-based staff. This arrangement would deploy small crews to travel the length of the pathway each day in gator-type vehicles with trash cans, brooms, etc. A crew of four workers and a working supervisor could cover up to eight miles of path by starting at the north and south ends, and meeting mid-way.

Broken glass on paths will require extra attention because it poses a special danger to children on the greenway. In addition, for cyclists, glass can be a greater problem on pathways than it is on streets, where it is normally crushed by vehicles and swept up by mechanical sweepers.

Winter greenway maintenance will also require special attention. Developing practices for keeping paths free of ice, without using chemicals in ways that are ecologically damaging, will be a challenge. Alternatives to salt—such as potassium chloride—should be used on pathways. Major pathways, especially segments that are sloping, shaded, or located on bridges, will all need to be kept cleared and their drainage carefully maintained.

Routine Maintenance Tasks:

-

Daily (7 days per week)

- Path sweeping with hand brooms

- Snow removal

- Litter pick-up

- Emptying trash and recycling receptacles

- Comfort station cleaning and resupply

-

Regular (Intervals TBD)

- Lawn mowing

- Flower bed maintenance

- Native plantings need relatively little maintenance; district staff should notify the Bronx River Conservation Crew of any problems they observe in these areas

-

As-needed, with Needs Identified in the Course of Daily Maintenance

In the course of daily maintenance, staff will identify items that require specialized materials, equipment, or trades, and submit a work order to the NYC Parks Bronx Borough's Shops or Forestry Unit or other City agencies, as appropriate.

- Asphalt patching

- Pavement markings maintenance

- Painting and graffiti removal

- Signage repair and replacement

- Light fixture maintenance (New York City Department of Transportation—NYCDOT)

- Tree pruning and care

- Comfort station repair

- Playground equipment repair

-

Periodic Maintenance Needs

All bridges must be inspected annually by qualified engineers. Inspection of the greenway's bridges will be performed by NYCDOT and paid for by NYC Parks. There will ultimately be five greenway bridge spans—four over the river itself, one over Amtrak, and one over the Bronx River Parkway. Current plans call for the bridges to be made from weathering steel, which develops a permanent coating and does not require painting.

Floating docks planned for Hunts Point Riverside Park and Starlight Park will also require regular inspection and repair (see boat launch map for a complete list of planned and existing boat launches). Buildings that are part of the greenway, including the boat storage building at Starlight Park, will require maintenance to be planned and budgeted into their normal operations.

Responsibilities of the Bronx River Conservation Crew

NYC Parks district staff do not normally maintain waterways and other natural and restored

areas. The Alliance has developed and continues to build the capacity of the Bronx River

Conservation Crew to care for the river and to continue the work of ecological restoration. As is

already the case, the Crew will have primary responsibility for:

- Maintaining the river and its banks (clearing blockages and removing debris)

- Maintaining natural vegetation areas

- Maintaining and monitoring restoration sites

- Additional restoration projects